Stories & interviews

Interview Jan van de Winkel

What does it mean to “crack the code of cancer and other serious diseases”? At the opening of Utrecht Science Week, Prof. Dr. Jan van de Winkel will share how immunotherapy, AI, and collaboration are key to groundbreaking advances in fighting and preventing cancer and other serious diseases.

Interview Peter Luijten

Peter Luijten, former Vice Dean of the Strategic Theme Life Sciences at Utrecht University and Professor of Functional Medical Imaging, retired from Utrecht University in October 2024. Throughout his career, he made significant contributions to the development of various medical technologies and innovative research at the Utrecht Science Park.

Interview Ruut van Rossen

Ruut van Rossen is a familiar face to many at Utrecht Science Park. In April 2024, after more than 40 years, he retired from Utrecht University. Over the past years, the Utrecht Science Park Foundation and other partners have worked closely and pleasantly with Ruut on numerous projects in the area. Ruut held various positions during his career, with the longest and final role being Head of Campus Management. We spoke with Ruut about his role in recent years, his contributions to Utrecht Science Park, and the key projects and developments that stood out to him the most.

Interview Robin Lechner

Robin is programme and event coordinator at UtrechtInc, which actually merges a lot. She makes programmes for starting entrepreneurs from the region, university employees and students. The programmes consist of lots of events, from very small events and coaching sessions to a big event for all startups in the community or during the Utrecht Science Week.

Interview Sharon Dijksma

Sharon Dijksma Mayor of van Utrecht about the Utrecht Science Park.

For me, Utrecht Science Park is a jewel. And a very vibrant jewel, too, because it helps to determine how the world of tomorrow will look through pioneering research, top-level education, excellent entrepreneurship, and smart start-ups and scale-ups in life sciences and health. Moreover, just a short walk away, you will find yourself in a green oasis of calm, including the country estates and the Unesco World Heritage Site of the Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie. It’s precisely this combination that, for me, makes it such a special and valuable place.

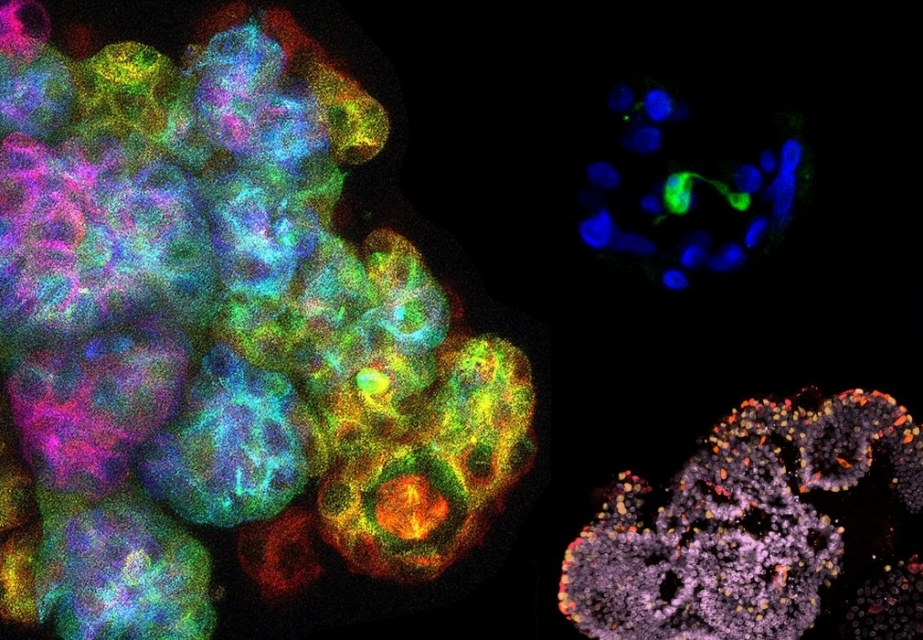

The revolutionary development of mini-organs

This is the story of the revolutionary development of mini-organs – organoids – and the countless ways they help us develop and implement personalized treatments. A story about the future of medicine from a group of scientists from Utrecht Science Park, who started this adventure out of… curiosity.

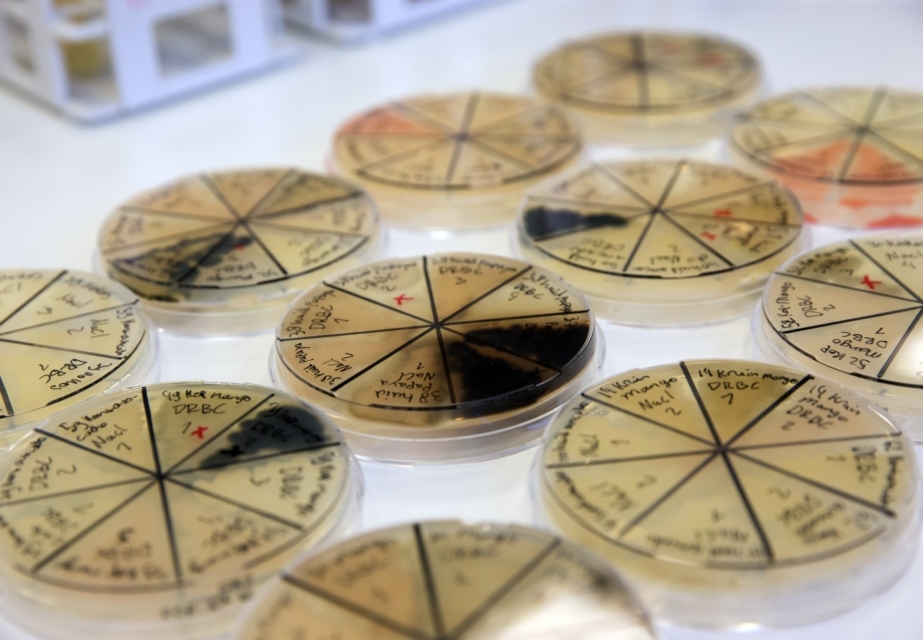

A collection of fungi as a treasure trove for the world

The Westerdijk Institute at Utrecht Science Park has the largest fungal collection in the world. Scientists are investigating the enormous range of possible applications of fungi. In the areas of health, agriculture, environment and industry. Read the unique story behind the importance of fungi and the groundbreaking research that is being done here at Utrecht Science Park.

Your own cells as medicine

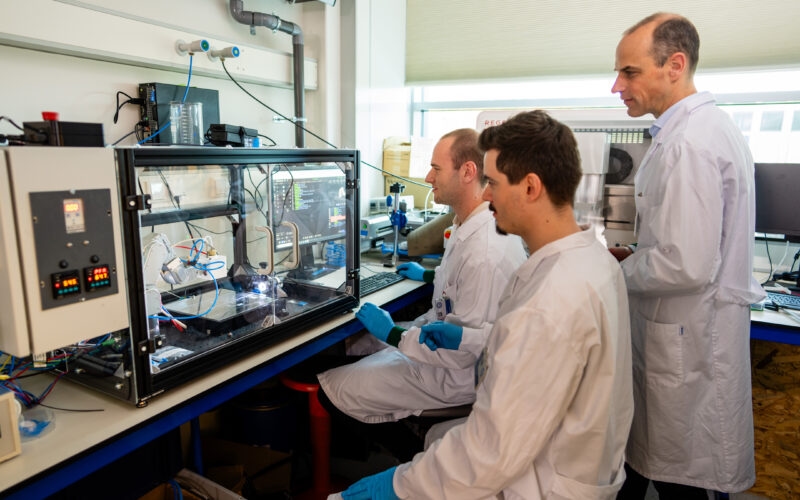

In Utrecht, there is a lot of knowledge about ‘regenerative medicine’. In regenerative medicine, we use natural processes to help the body recover after damage. Partners at the Utrecht Science Park, such as Utrecht University, UMC Utrecht and the Hubrecht Institute work together in an interdisciplinary way to arrive at better and faster solutions. Regenerative Medicine in Utrecht (RMU) focuses on three themes: cardio-renal tissue regeneration, musculoskeletal tissue regeneration and stem cell and organoid biology. Read more here and watch the film about this unique collaboration.

Collaboration between WKZ and Princess Máxima Center

The collaboration between the Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital (WKZ) and the Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology at the Utrecht Science Park is a powerful example of integrated care and research at the highest level, with the aim of providing the best possible treatment for sick children in the Netherlands.